In Persuit of a Dream

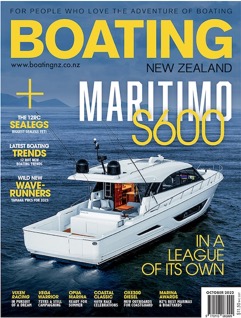

10 22 Topic : Yacht Reviews

In pursuit of a Dream.

A collaboration between companies in the marine sector has resulted in a new lease of life for this 12-metre raceboat — and will hopefully see her go all the way to Japan in pursuit of a childhood dream.

Project manager and lifelong sailor Scott Fickling bought this Guillaume Verdier- designed Class 40, first launched in 2008 as Desafio Cabo de Horno, with an eye to refitting her for short-handed racing. The plan was just about to swing into action a range of friends and contacts in the marine industry.

“Since I was about nine and sailing my Optimist at Torbay, I’ve wanted to do the [two-handed] Melbourne to Osaka race,” he says. “I thought it was a great chance to take an older boat and make it new again. I spent my late teens and early twenties working as a rigger and I had some ideas about how I wanted to set it up.”

The initial goal was the 2024 Melbourne–Osaka, but with covid complications pushing out both the race start and the rebuild, that’s now 2025, seven years since the event was last held. That’s provided time for a reimagining and rebuild of the boat, especially focusing on improving its speed in light airs.

“Being an Open class boat, we knew it would be sticky in the light, and there’s lots of that in the Melbourne to Osaka, because you sail right over the equator,” Fickling says. After speaking to Campbell Field about predicted weather conditions, Fickling consulted designer Kevin Dibley to find out what could be done to best maximise the boat’s performance.

“We didn’t have an initial 3D [design] package for the boat, but once we got that and loaded it into Maxsurf we could work out the basic hydrostatics with the original sail plan,” Dibley when the first covid lockdowns hit in 2020, but in late January this year, after nearly two years of work, she finally re-entered the water as the bright-pink-liveried Vixen Racing.

The 40-footer first came to New Zealand while being sailed two-handed round the world in the 2010 Global Ocean Race by Ross and Campbell Field, under the name Buckley Systems. The pair were leading the race when Ross Field injured his back and they were forced to withdraw, not long after leaving the Wellington stopover.

The boat then stayed in New Zealand and was sailed under the name Hupane, but for the past few years has been sitting unused in Auckland’s Viaduct Harbour. When Fickling saw Hupane sitting there, looking lonely and unloved, he saw the opportunity to make a long-held dream come true, through a collaboration with says. “Then we worked with Bart [rigger Richard Bearda] and Stu Bannatyne at Doyle Sails to work out how we could increase the sail area, but maintain stability and balance, and came up with a good package.”

The overall sail area has been increased by around 13 per cent, including a main with a massive top batten, and the rig has been replaced with a new, longer carbon version. The basic hull shape, fixed keel and twin rudders were left the same, but the bow was remodelled to incorporate a larger, fixed bowsprit instead of the original canting prod, along with some different systems for running sails.

“The big thing for Melbourne–Osaka is we wanted to keep the boat simple, so no canting keel, and we wanted twin rudders for redundancy,” Fickling says. Instead, the boat has 600 litres of water ballast to ensure its performance to windward.

The structural aspects of the alterations were engineered by Pete Lawson of Hauraki Design Consultancy, while the actual building was carried out by Shaun Harrison of Carbon Developments on the Whangaparaoa Peninsula, near the boat’s current home at Gulf Harbour. Harrison, a long-term friend of Fickling’s, has worked for five America’s Cup campaigns and was happy to lend a hand to make the changes to Vixen.

“The original boat is glass over foam, but the bowsprit is carbon and a lot of the new components we added were carbon, to save weight,” he says. He also enjoyed the collaborative nature of the rebuild. “It was a good bunch of guys and a great project to be involved with.”

Much of the interior was stripped out and the cockpit remodelled to add a central power winch on a pedestal. A new Yanmar engine was fitted by Marine Propulsion and all-new electrical systems installed by Beacon Marine.

“When we were working out how the boat should be set up, we talked to people like Stu [Bannatyne] and [round-the-world sailor and Olympian] Sharon Ferris-Choat — people who have done a lot of miles offshore,” Fickling says.

Little details like the chart table canting to a 45-degree angle will make racing over long distances easier and more efficient. The interior is pleasantly non-cave like, rather than the wet, black carbon cave you might expect from a dedicated race boat.

Dibley also worked with Fickling and his wife Tash to give the boat a completely new look with striking hot-pink vinyl.

“We went through a few artists — we worked up a Picasso version and a Dali version before Tash decided on the pink colour scheme,” Dibley laughs. It’s certainly striking — although you’d have to be careful not to be over the line at the start, because that pink prod would give you away.

So far the boat has competed in a number of SSANZ events, and Fickling and his regular crew James Tucker will line up for the two-handed Round the North Island race next year. Vixen won the Yates Cup 230-mile race in July, sailed four-up with a crew including women’s national keelboat champion and highly experienced short- handed sailor Sally Garrett. Other top female sailors such as Ferris-Choat and Bex Gmuer Hornell have also been sailing the boat.

“It was good having four of us for the Yates Cup,” Fickling says. “For a short-handed boat it’s got a huge amount of sail, so it keeps the crew quite busy.”

The current wardrobe includes a number one and two jibs, a structured luff cableless code zero, three asymmetric sails, a staysail and storm sail, “which we use a lot. Three-headed sailing is quite new to me, but we’ve had some great runs using with A2, J2 and the staysail inside it,” Fickling says.

The next year or so is a shake-down stage, finding out what worked and what still needs to be altered and adjusted. “Every sail is a chance to iron out a few wrinkles. We have something new on the list every time we come in.”

Obviously, the project hasn’t been cheap, but as Fickling says, “We’ve got a pretty serious goal, and we need a serious bit of equipment.”

Fickling says it was important to him to do the work in New Zealand and involve mostly small companies from the local marine industry. “I really wanted to show that this kind of thing can still be done in New Zealand. Kiwis build such great boats and these guys all work really well together."

“Since I was about nine and sailing my Optimist at Torbay, I’ve wanted to do the [two-handed] Melbourne to Osaka race,” he says. “I thought it was a great chance to take an older boat and make it new again. I spent my late teens and early twenties working as a rigger and I had some ideas about how I wanted to set it up.”

The initial goal was the 2024 Melbourne–Osaka, but with covid complications pushing out both the race start and the rebuild, that’s now 2025, seven years since the event was last held. That’s provided time for a reimagining and rebuild of the boat, especially focusing on improving its speed in light airs.

“Being an Open class boat, we knew it would be sticky in the light, and there’s lots of that in the Melbourne to Osaka, because you sail right over the equator,” Fickling says. After speaking to Campbell Field about predicted weather conditions, Fickling consulted designer Kevin Dibley to find out what could be done to best maximise the boat’s performance.

“We didn’t have an initial 3D [design] package for the boat, but once we got that and loaded it into Maxsurf we could work out the basic hydrostatics with the original sail plan,” Dibley when the first covid lockdowns hit in 2020, but in late January this year, after nearly two years of work, she finally re-entered the water as the bright-pink-liveried Vixen Racing.

The 40-footer first came to New Zealand while being sailed two-handed round the world in the 2010 Global Ocean Race by Ross and Campbell Field, under the name Buckley Systems. The pair were leading the race when Ross Field injured his back and they were forced to withdraw, not long after leaving the Wellington stopover.

The boat then stayed in New Zealand and was sailed under the name Hupane, but for the past few years has been sitting unused in Auckland’s Viaduct Harbour. When Fickling saw Hupane sitting there, looking lonely and unloved, he saw the opportunity to make a long-held dream come true, through a collaboration with says. “Then we worked with Bart [rigger Richard Bearda] and Stu Bannatyne at Doyle Sails to work out how we could increase the sail area, but maintain stability and balance, and came up with a good package.”

The overall sail area has been increased by around 13 per cent, including a main with a massive top batten, and the rig has been replaced with a new, longer carbon version. The basic hull shape, fixed keel and twin rudders were left the same, but the bow was remodelled to incorporate a larger, fixed bowsprit instead of the original canting prod, along with some different systems for running sails.

“The big thing for Melbourne–Osaka is we wanted to keep the boat simple, so no canting keel, and we wanted twin rudders for redundancy,” Fickling says. Instead, the boat has 600 litres of water ballast to ensure its performance to windward.

The structural aspects of the alterations were engineered by Pete Lawson of Hauraki Design Consultancy, while the actual building was carried out by Shaun Harrison of Carbon Developments on the Whangaparaoa Peninsula, near the boat’s current home at Gulf Harbour. Harrison, a long-term friend of Fickling’s, has worked for five America’s Cup campaigns and was happy to lend a hand to make the changes to Vixen.

“The original boat is glass over foam, but the bowsprit is carbon and a lot of the new components we added were carbon, to save weight,” he says. He also enjoyed the collaborative nature of the rebuild. “It was a good bunch of guys and a great project to be involved with.”

Much of the interior was stripped out and the cockpit remodelled to add a central power winch on a pedestal. A new Yanmar engine was fitted by Marine Propulsion and all-new electrical systems installed by Beacon Marine.

“When we were working out how the boat should be set up, we talked to people like Stu [Bannatyne] and [round-the-world sailor and Olympian] Sharon Ferris-Choat — people who have done a lot of miles offshore,” Fickling says.

Little details like the chart table canting to a 45-degree angle will make racing over long distances easier and more efficient. The interior is pleasantly non-cave like, rather than the wet, black carbon cave you might expect from a dedicated race boat.

Dibley also worked with Fickling and his wife Tash to give the boat a completely new look with striking hot-pink vinyl.

“We went through a few artists — we worked up a Picasso version and a Dali version before Tash decided on the pink colour scheme,” Dibley laughs. It’s certainly striking — although you’d have to be careful not to be over the line at the start, because that pink prod would give you away.

So far the boat has competed in a number of SSANZ events, and Fickling and his regular crew James Tucker will line up for the two-handed Round the North Island race next year. Vixen won the Yates Cup 230-mile race in July, sailed four-up with a crew including women’s national keelboat champion and highly experienced short- handed sailor Sally Garrett. Other top female sailors such as Ferris-Choat and Bex Gmuer Hornell have also been sailing the boat.

“It was good having four of us for the Yates Cup,” Fickling says. “For a short-handed boat it’s got a huge amount of sail, so it keeps the crew quite busy.”

The current wardrobe includes a number one and two jibs, a structured luff cableless code zero, three asymmetric sails, a staysail and storm sail, “which we use a lot. Three-headed sailing is quite new to me, but we’ve had some great runs using with A2, J2 and the staysail inside it,” Fickling says.

The next year or so is a shake-down stage, finding out what worked and what still needs to be altered and adjusted. “Every sail is a chance to iron out a few wrinkles. We have something new on the list every time we come in.”

Obviously, the project hasn’t been cheap, but as Fickling says, “We’ve got a pretty serious goal, and we need a serious bit of equipment.”

Fickling says it was important to him to do the work in New Zealand and involve mostly small companies from the local marine industry. “I really wanted to show that this kind of thing can still be done in New Zealand. Kiwis build such great boats and these guys all work really well together."